Table of Contents

When I was eleven, I wrote a story about a girl who could talk to shadows. I gave her a mom who ran a bakery, a best friend who wore too much eyeliner, and—for reasons still baffling—a jade bracelet that glowed ominously during thunderstorms. Guess what I never did? Exactly. The bracelet never came back, never glowed again. No payoff, no reveal, just hanging there glowing inertly until my vaguely tragic monologue wrapped things up. My poor seventh-grade teacher deserved better.

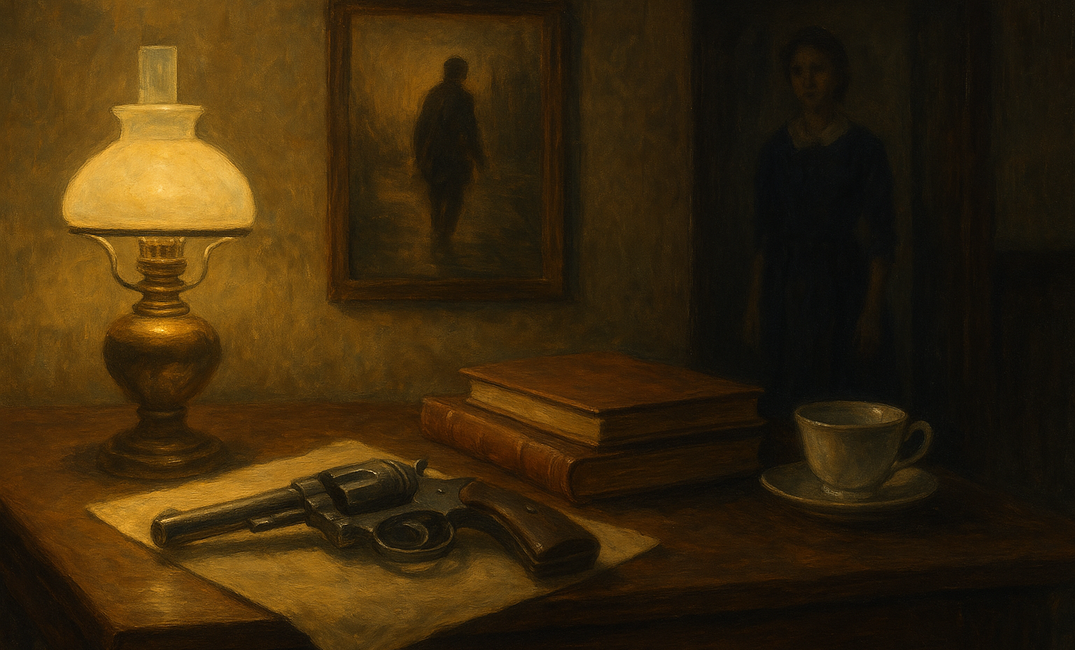

Anton Chekhov, literary realist extraordinaire and man of zero narrative chill, famously advised: "If you show a gun on the wall in Act One, it must go off by Act Three." At face value, this sounds straightforward—avoid random clutter. But Chekhov's Gun isn't just about minimalist aesthetics; it's about the emotional contract you make with your readers. If you highlight an object, line, or character trait, your reader instinctively expects it to matter. Fail that promise and readers feel cheated. Fulfill it, and you've built something powerful.

Ready to make every planted detail pay off? Draft your next twist in Sudowrite

But don’t confuse Chekhov’s Gun with "every detail must be relevant." You can mention wallpaper without peeling it off to reveal a corpse. But if your character wakes up every morning whispering to a stuffed bear named Nikolai, that bear better matter. Emotionally or narratively. Ideally both.

The Simple Stuff (Writing Tricks That Matter)

It's easy to get distracted with fancy stuff, so let's start here: readers are wandering in the dark. Blindfolded, senses limited. You have a flashlight, to highlight one thing at a time. Or you're describing a scene through a radio. The point is, they only experience what YOU choose to show them!

If you know what you're doing, you'll show them the important stuff that matters. If you don't know what you're doing, you'll show them a bunch of random crap, and as soon as they realize they can't trust your narrative, they'll give up in frustration.

There are two critical mistakes most authors make:

1. They show everything too early. They explain everything, highlight everything. Then the action just... plays out exactly how you set it up. There's no magic or suspense or intrigue - you gave away the ending too early. There was never any question or mystery.

2. They don't show enough. In this case, every incident feels like random luck or chance, the plot is a messy, things happen but there isn't any buildup or crescendo or dramatic action.

Here's the big secret to writing dramatic tension: never speculate or mention the thing that's true, always guess or speculate about something else that could be true (red herring). At the same time, you need your conclusion to feel inevitable so you DO need to justify the final conflict. You need to make sure you've mentioned all the things that are critical to reach your ending. They need to be present, but they should be discounted or discredited. Here's a dangerous thing but don't worry, it's broken. The safety is on. It's locked up. Don't make it a big thing. This is Chekhov’s Gun: the dangerous thing that will cause an explosive ending, that was present the whole time but understated or ignored.

How do you show the dangerous thing and still have the ending be a real surprise? How do you pull of twists and reveals without them falling flat or being too predictable?

Below is in-depth exploration of Chekhov’s Gun and foreshadowing, enriched with references, practical methods, and examples from both classic and contemporary literature. By the end, you should have enough tools to plan, rewrite, and refine your setups and payoffs in ways that feel robust, thematically sound, and unforgettable.

Need help balancing red herrings and real clues? Try Sudowrite’s Focus Mode to outline smarter, faster

The Many Faces of Chekhov’s Gun

Foreshadowing is the art of planting seeds early so they blossom when the narrative needs them most. This might take the shape of a repeated phrase, an offhand warning, an innocuous scene that resonates powerfully in retrospect. It’s how you build tension and coherence.

It’s how your climax feels earned rather than forced. Yet many writers misunderstand how to use Chekhov’s Gun or how to weave in foreshadowing effectively—either by telegraphing their intentions so obviously that the twist is DOA, or by dropping random “guns” that never fire, leaving readers frustrated at the false promises.

Chekhov’s Gun is about trust.

It's a promise to your readers that you’re not wasting their time or emotional energy. If an object, a detail, or even a line of dialogue stands out, it’s either relevant or a deliberate misdirection. In both cases, you as the author are actively engaging the reader's attention.

Explore story structure that actually works to see how to build turning points that matter.

Historical Context

Anton Chekhov was a Russian playwright and short-story writer known for his understated, character-driven dramas—“The Seagull,” “Uncle Vanya,” “The Cherry Orchard.” He believed extraneous detail in a story was akin to lying to the reader.

He insisted that every narrative element must serve a unifying purpose (dramatic, thematic, or emotional). He famously wrote about the “gun on the wall” to illustrate that if an author draws attention to something, an audience naturally expects it to matter. If it doesn’t, the tension deflates or the story’s aesthetic wholeness is ruined.

The concept resonates with modern narrative theory, especially in screenwriting (where setup and payoff is a bedrock principle). Robert McKee’s “Story” frames it as the law of “Conservation of Detail,” encouraging writers to revolve scenes around essential elements. John Truby, in “The Anatomy of Story,” urges authors to think in terms of consistent cause-and-effect. Syd Field’s approach to planting and payoff in screenplays likewise warns that a planted detail, once introduced, must eventually bear fruit.

Yet Chekhov’s insight goes further than the usual “don’t have a random object that never reappears.” It’s about emotional unity, and narrative compression. By deliberately foregrounding an object, emotion, or line of dialogue, you create an implied contract with the reader: this is important—keep your eyes on it. If you never deliver, you break that contract.

- Chekhov’s Gun is a principle of economy.

- Foreshadowing is the method by which that principle often manifests.

Foreshadowing sets up future events or revelations in ways the reader can’t fully interpret until the payoff arrives. When done right, foreshadowing yields that “aha” moment for readers. When done clumsily, it becomes so overt that the ending feels telegraphed or it remains so hidden that the climax feels unprepared.

Foreshadowing vs. Foreshouting (Please Stop Yelling)

Effective foreshadowing feels inevitable, not predictable. It's subtle, creeping quietly into your subconscious, waiting for the payoff to explode with resonance.

Foreshadowing is how you build tension without waving a neon sign that says BIG DRAMATIC TWIST INCOMING.

It’s a character saying, “I hate hospitals,” three chapters before they’re forced to break into one. It’s the dog barking at the basement door long before we know what’s buried down there. It’s the offhand mention of a broken wristwatch, forgotten until it starts ticking again.

The best foreshadowing doesn’t predict—it recontextualizes. It makes the reader feel smart when they get to the twist. Not surprised, exactly, but satisfied. Like all the breadcrumbs finally formed a shape.

Foreshadowing can take several forms:

It can be overt, as in the prophecy model (for instance, Shakespeare’s witches in “Macbeth,” who literally tell Macbeth he will be king). It can be subtle, as in the color red signifying supernatural activity in “The Sixth Sense.” It can also be an emotional or thematic echo, such as the repeated references to drowning in Kate Chopin’s “The Awakening,” culminating in Edna’s final swim.

Foreshadowing is the quiet chill in the air; it's not the villain shouting, “SEE YOU AT THE CLIMAX!”

- Foreshadowing: A character noticing a dead bird outside their window.

- Foreshouting: A dream sequence explicitly warning everyone dies soon.

The universal principle is this: a detail or motif introduced early must transform in meaning or significance by the story’s climax, or at least by a critical turning point. This metamorphosis can be literal—like a gun that finally discharges—or metaphorical—like a single line of dialogue that later becomes the hinge of a character’s epiphany.

Chekhov's Gun can be any prominent detail, whether tangible or emotional:

- Literal Gun: A knife tucked under floorboards (think Dostoevsky's "Crime and Punishment").

- Emotional Gun: A character claiming, "I'd never lie to you." (They inevitably will.)

- Thematic Gun: A recurring phrase or motif that grows in significance (like the line "Survival is insufficient" from "Station Eleven").

But not every detail must explode dramatically. Subtle emotional payoffs can be equally impactful.

Stuck on a subtle clue? Generate the perfect breadcrumb with Sudowrite

Conflict Multipliers

If you need to explain inside a scene, why this scene is challenging... it's probably too late. Your job as an author is to make things interesting but never letting your characters just freely accomplish goals with no resistance. It's your JOB to create resistance; both interior and exterior - physical and emotional.

You need to bring your protagonist to a place where they will choose to do things that they have always avoided before. So before they need to do a thing, you create a much earlier setup where they avoid or resist the same thing. It can be an internal or external limitation; a fear or prohibition.

Types of Foreshadowing You Can Actually Use

- Direct Foreshadowing: Clear warnings, often conversational ("I can't swim," before a water-based crisis).

- Indirect Foreshadowing: Symbolic imagery—storms, shadows, a recurring animal.

- Prophetic Irony: Casual comments gaining sinister meaning later ("I'd kill for some peace").

- Red Herrings: False leads—think Agatha Christie; use sparingly to avoid reader distrust.

- Thematic Echoes: Repeated symbols or phrases evolving in meaning.

In a murder mystery, where the whole story revolves around solving the case, you can't make things too obvious; so you must have plausible alternatives... and this is true for most stories. In order for unexpected events to play out, we need some expected events that do not play out. You need just enough information for these things to happen or not happen - for the happy ending to be in doubt so that the stakes are real and failure is an option - to deliver a satisfying conclusion.

Need a name for that ominous stuffed bear or a storm‑battered ship? Find the perfect character name

Real, Specific, Gut-Wrenching Examples

Consider F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby.” The billboard of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg looms over the valley of ashes. While not a literal “gun,” it’s introduced repeatedly as an ominous symbol. By the end, George Wilson interprets it as the eyes of God, fueling his misguided vengeance. The sign “fires,” thematically, revealing the moral emptiness overshadowing the characters. That’s Chekhov’s Gun as metaphor.

In Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Never Let Me Go,” subtle references to donations, “Madame,” and how the guardians speak of “special” students form a puzzle. By the time we learn the devastating truth, each earlier hint crashes into place. Ishiguro doesn’t wave a sign that says “these kids are clones.” He trickles the hints in daily interactions and quiet remarks, building emotional conflict instead of just unveiling a plot twist.

In “Atonement” by Ian McEwan, the letters and the fountain scene early on become the key to the entire tragedy. The narrative invests these objects and moments with tension, so when they re-emerge in new contexts, the heartbreak intensifies. The payoff isn’t a literal gun firing—it’s a revelation that changes how we interpret everything that came before.

Here are a few more examples. Challenge yourself to find more!

- The Prestige: Christopher Nolan meticulously plants every clue—the bird trick, the drowning tank, the pile of hats—so when it clicks, your jaw drops with inevitability.

- Of Mice and Men: Lennie’s fascination with soft things and accidental harm isn't accidental—it's building inexorably toward tragedy. The final disaster devastates you precisely because it feels inevitable.

- The Haunting of Hill House (Netflix): The Bent-Neck Lady isn't just creepy set-dressing. Her reveal retroactively reframes every scene, twisting terror into heartbreaking tragedy.

- Knives Out: The twist isn't hidden—it’s right in front of you. Rian Johnson shows you exactly what happened but tricks your assumptions. This kind of misdirection is masterful foreshadowing.

- We Have Always Lived in the Castle: Merricat's rituals seem whimsical until you recognize their sinister psychological implications. Shirley Jackson foreshadows emotional horror rather than obvious twists.

How to Plant a Gun Without Making It Obvious

Want subtlety, not obviousness? Here’s your practical blueprint:

- Introduce Early, Casually: The earlier the setup, the less suspicious.

- Natural Placement: Hide the clue within everyday detail.

- Multiple Meanings: Let clues have innocuous interpretations.

- Organic Emergence: Let clues appear in emotional or action scenes naturally, not artificially.

- Make it Ordinary: Readers shouldn’t suspect it's significant at first glance.

- Bury it in Action or Emotion: Hide the detail naturally within compelling scenes.

- Use it Unexpectedly: The hidden dagger doesn't have to kill—it might open a secret compartment.

Let’s say you’ve got a character who’s afraid of drowning. Easy foreshadowing, right? They’ll fall off a boat later. Or maybe they won’t. Maybe their fear makes them stop someone else from drowning. Maybe it’s a misdirect. That’s fine—so long as the setup means something.

Most authors discover their Chekhov’s Gun in revision. Early drafts are for exploring, messing up, and letting random details appear. Once you identify the crucial pieces in your story’s endgame, you revise backward to plant them properly.

Characters That Feel Real: The Art of Crafting Memorable Protagonists goes deeper on how emotional stakes and internal growth can supercharge your reveals.

Revision Strategy: Hunt, Plant, Polish

A practical approach is to do a thorough read focusing on each major turning point, listing any object, trait, or line that influences the climax. Then you check earlier chapters for opportunities to place or emphasize that element. This ensures the detail doesn’t appear out of nowhere. Alternatively, if you find an element that readers might assume is important but actually isn’t, you can either cut it or transform it into something thematically relevant.

Most foreshadowing crystallizes in revision:

- List crucial climax elements.

- Backtrack to plant subtle clues.

- Ensure details appear naturally, not forcibly emphasized.

- Cut or repurpose “false guns” that promise importance but never deliver.

If you’re writing a mystery or thriller, you might keep a spreadsheet of every clue and red herring, ensuring they’re introduced in chronological order, each repeated enough to be memorable but not suspiciously hammered in. Think of how meticulously Agatha Christie interweaves small, easily overlooked hints that all come roaring back in Poirot’s big reveal.

When polishing those revisions: Use Sudowrite’s Rewrite tool to tighten foreshadowing

Types of Foreshadowing (Because We’re Not Amateurs)

- Visual: A necklace, a weapon, a broken photo frame.

- Verbal: "Nothing could ruin this day." (Bold of you to say.)

- Situational: A storm coming. A power outage mentioned in passing.

- Symbolic: A wilting flower, a bird slamming into a window, a leak that won’t stop.

- Structural: Parallel scenes, repeated lines, callbacks.

Use sparingly. You’re not writing a riddle. You’re building a bomb with a very slow fuse.

Strategic Foreshadowing: Weaving Tension Through Your Novel

Tension emerges from the feeling events are hurtling toward a crisis we can’t fully predict yet. To sustain it:

- Echo References: Repeat phrases or images subtly across scenes, each recurrence growing darker or more significant.

- Delayed Exposition: Reveal backstory gradually, reframing earlier details with each new revelation.

- Contrasting Viewpoints: Multiple POV characters noticing (or ignoring) the same detail enriches reader suspense.

The Emotional Gun: Quietly Devastating

Not all payoffs are explosions. Some are quiet heartbreaks.

- A father who can’t say “I love you” dies before he gets the chance.

- A child’s imaginary friend vanishes the night their parents divorce.

- A character talks about fear of being forgotten—and ends up with an unmarked grave.

These are the guns that leave bruises instead of bullet holes.

When to Subvert (and When Not To)

You can break the rule. Of course you can. You can hang the gun on the wall and never fire it—as long as that’s the point.

- The Leftovers makes narrative absences part of its theme. What matters isn’t payoff—it’s longing.

- Annihilation introduces details that go nowhere because reality is fracturing.

But if you’re not doing it on purpose? It feels like laziness. Or worse—like you forgot your own plot.

Firing the gun, literally or metaphorically, is more than tying up a plot thread. It’s giving your story emotional resonance. Readers crave that sense of everything snapping into place. It’s the difference between a random surprise and a richly foreshadowed climax that leaves them in awe.

By fulfilling the promise, you reaffirm narrative coherence. This is deeply satisfying because humans love patterns. We want to see cause and effect. We want to trust that an author who points to a locked cabinet on page 25 will open it by page 300. Breaking that trust can be done for a purposeful effect—like an open-ended or existential story—but nine times out of ten, fulfilling it is the better choice if you want emotional closure.

Subversion can be brilliant if executed with thematic weight. You might introduce a loaded gun that is never fired to highlight futility, or because the real threat was intangible all along. For example, in “Waiting for Godot,” Beckett introduces the concept of “Godot,” but he never appears, which is the entire existential statement. Or in certain postmodern works, the Chekhov’s Gun is left on the wall as a commentary on narrative expectations. This only works if the story acknowledges the un-fired gun in a way that resonates thematically rather than leaving it to negligence.

Finally, you can reassign the “gun” at the last minute. The detective’s suspicion focuses on the letter opener, but the actual murder weapon is the teal scarf glimpsed in a single passing sentence. Done well, it’s a game-changer that re-evaluates prior details. Done poorly, it’s a cheap trick. The difference is whether you gave enough subtle presence to that scarf for the audience to realize they could have seen it coming.

Making Every Promise Count

Chekhov’s Gun and foreshadowing are cornerstones of narrative architecture. They guide what you emphasize and how you reward reader attention. They ensure that the random jade bracelet on your protagonist’s wrist (looking at my younger self) means something—maybe it’s the key to the final puzzle, or a cursed artifact that dooms her family, or a symbol of inheritance that has to be relinquished at the emotional climax.

The point is that the detail stands for more than itself. It becomes a narrative promise, a seed that blooms when you want it to. And in that moment of bloom—be it a mind-blowing twist or a quiet heartbreak—you create that sense of “Of course. It had to be this way.” That’s the real magic. It’s not about illusions or shock. It’s about crafting a story so cohesive, so carefully orchestrated, that your reader closes the final page feeling both surprised and satisfied.

So pay attention to your guns, your locked boxes, your subtle gestures, your recurring lines. Decide which ones matter and give them a final, resonant purpose. Everything else can get cut or repurposed. Because in the end, Chekhov was right: if you hang a detail in plain sight, your readers will absolutely expect it to fire. Honor that expectation—and watch your story’s tension and emotional impact skyrocket.

Ready to fire every “gun” you plant? Start your free trial of Sudowrite today

Get to your final draft, faster

Our Write feature can generate your next 100-500 words in your style, helping you finish drafts in record time. Choose from multiple options. Edit as you like.

Polish without losing your voice

Using Rewrite, you can refine your prose and still be your unique self, by choosing from multiple AI-suggested revisions designed to capture your voice.

Paint descriptions with more pop

Describe helps you make sure readers feel like they’re really there, proposing new ideas for enriching scenes — whenever some are needed.

Build out scenes with ease

With Expand, you can smoothly and quickly build out scenes, slow pacing, and add immersive detail, all without breaking your flow.

Effortlessly outline your story

Story Bible gets you from idea to outline in a flash, helping you structure plot, character arcs, and themes — step-by-step.

Revise faster with instant feedback

Sudowrite’s Feedback tool delivers AI-powered suggestions for improvement on demand, as often as you need, and without complaint. Make room, beta readers.

Banish writers block – forever!

Creative prompts from Brainstorm keep you flowing, and the tool learns more about how you think, the more you use it. Bye bye, blinking cursor.